The Parallax View

| The Parallax View | |

|---|---|

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Alan J. Pakula |

| Screenplay by | David Giler Lorenzo Semple Jr. |

| Based on | The Parallax View by Loren Singer |

| Produced by | Alan J. Pakula |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Gordon Willis |

| Edited by | John W. Wheeler |

| Music by | Michael Small |

Production companies |

|

| Distributed by | Paramount Pictures |

Release date |

|

Running time | 102 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

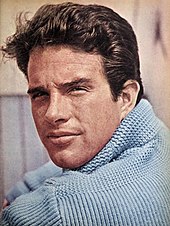

The Parallax View is a 1974 American political thriller film starring Warren Beatty, with Hume Cronyn, William Daniels and Paula Prentiss in support. Produced and directed by Alan J. Pakula, its screenplay is by David Giler and Lorenzo Semple Jr., based on the 1970 novel by Loren Singer.[2] The story concerns a reporter's investigation into a secretive organization, the Parallax Corporation, whose business is political assassination.

Plot

[edit]TV journalist Lee Carter witnesses the assassination of U.S. senator and presidential aspirant Charles Carroll atop the Seattle Space Needle. The suspected killer, a waiter, is killed during the pursuit. The real killer, disguised as a waiter, escapes. The assassination is officially determined to have been the work of a single man acting alone. Six witnesses die over the next three years. Carter fears she will be next, and goes to ex-boyfriend Joe Frady, an investigative newspaper reporter in Oregon, for protection; he turns her away. Shortly afterwards Carter is found dead; the death is ruled to be suicide from alcohol and barbiturate overdosing.

Feeling guilty about disregarding Carter's pleas and suspicious about her death, Frady investigates the drowning death of Judge Arthur Bridges - another witness - in the nearby small town of Salmontail. Wicker, the local sheriff, takes Frady to place below a dam where Bridges died. Wicker attacks Frady as the floodgates open and Wicker drowns. At Wicker's home, Frady discovers documents from the Parallax Corporation, an organization recruiting "security" operatives. Frady takes a Parallax personality test document from Wicker's home to a local psychology professor, Nelson Schwartzkopf. Schwartzkopf determines the test is used to identify homicidal psychopaths and gives it to a known psychopath to learn the "correct" answers.

Frady meets with Austin Tucker, an aide to Carroll and another witness, on Tucker's yacht; Tucker has survived two murder attempts since the assassination. Tucker saw the real assassin and gives Frady an image of the assassin in disguise. A bomb destroys the yacht. Tucker is killed, and Frady - sitting at the bow - is thrown into the water and presumed killed. Frady tells his editor, Bill Rintels, that he will use his official death and a pseudonym to infiltrate Parallax. A few days later, Frady is recruited for training by Parallax official Jack Younger.

Frady visits Parallax's Los Angeles headquarters where he is observed for reactions to montages of disturbingly edited and subliminal still photographs and images that juxtapose pro- and anti-American attitudes. Frady spots Carroll's assassin while leaving and follows the assassin to Hollywood Burbank Airport, who puts a bomb aboard a passenger jet in checked baggage. Frady boards the flight, mistakenly believing the assassin to be on board, and finds another United States senator who is also considering running for president. Frady surreptitiously warns a flight attendant. The jet returns to the airport and is evacuated before it explodes.

Younger confronts Frady about the latter's alias. Frady's cover story and a second alias mollifies Younger. Later, at the newspaper office, Rintels listens to a recording of this conversation and stores it with other evidence. That evening, Rintels is killed by poisoned food delivered by the assassin, disguised as a deli delivery boy. The evidence is gone by the time Rintels body is discovered.

Frady goes to Parallax's office in Atlanta, where he has been assigned a security position. There, he follows the assassin to a rehearsal for a political rally for another presidential aspirant, Senator George Hammond. Frady chases the assassin. Hammond is killed by an unseen sniper. Frady finds the rifle on the catwalks and then spotted by security. Frady flees realizing he is being framed as a scapegoat and is killed by security.

Six months later, another official investigation reports that Frady was a paranoid lone gunman who killed Hammond out of a misguided sense of patriotism.

Cast

[edit]

- Warren Beatty as Joseph Frady

- Paula Prentiss as Lee Carter

- Hume Cronyn as Bill Rintels

- William Daniels as Austin Tucker

- Kenneth Mars as former FBI agent Will Turner

- Walter McGinn as Jack Younger

- Kelly Thordsen as Sheriff L. D. Wicker

- Jim Davis as Senator George Hammond

- Bill McKinney as Parallax assassin

- Stacy Keach Sr. as Commission Spokesman #1

- Anthony Zerbe as Professor Nelson Schwartzkopf (Uncredited)

- William Jordan as Tucker's aide

- Edward Winter as Senator Jameson

- Chuck Waters as Thomas Richard Linder

- Earl Hindman as Deputy Red

- William Joyce as Senator Charles Carroll

- Jo Ann Harris as Chrissy, Frady's girl

- Doria Cook-Nelson as Gale from Salmontail

- Ford Rainey as Commission spokesman #2

- Richard Bull as Parallax goon

Production

[edit]Development

[edit]The film is based on a novel by Loren Singer. The novel followed witnesses of John F. Kennedy's assassination who were subsequently killed, but in the screenplay they see an assassination more like that of Robert F. Kennedy.[3] Robert Towne did an uncredited rewrite of the screenplay.[4]

Cinematography

[edit]Frady is often filmed from great distances, suggesting that he is being watched.[3]

Montage

[edit]Most of the images used in the assassin training montage were of anonymous figures or important historical figures, featuring among others Richard Nixon, Adolf Hitler, Pope John XXIII, and Lee Harvey Oswald (the photograph that captures the moment Oswald is shot). The montage also uses drawings by Jack Kirby from Marvel Comics' Thor. They are juxtaposed with caption cards showing the words 'LOVE', 'MOTHER', 'FATHER', 'HOME', 'ENEMY', 'HAPPINESS', and 'ME'. The montage "captures the confusion of post-Kennedy America" by demonstrating the decay of values and longstanding traditions.[5] It has been compared to the brainwashing scene in Stanley Kubrick's 1971 film A Clockwork Orange.[6][5]

Critical reception

[edit]At the time of its release, The Parallax View received mixed reactions from critics, but the film's reception has been more positive in recent years. On Rotten Tomatoes the film has an approval rating of 87% based on 45 reviews, with an average rating of 7.8/10. The site's critics consensus says, "The Parallax View blends deft direction from Alan J. Pakula and a charismatic Warren Beatty performance to create a paranoid political thriller that stands with the genre's best."[7] On Metacritic the film has a weighted average score of 65 out of 100 based on 12 critics, indicating "generally favorable reviews".[8]

Roger Ebert of The Chicago Sun-Times gave the film three out of four stars upon its release. While Beatty offered a good performance in an effective if predictable thriller, Ebert said the actor was not called upon to exercise his full talents. Ebert also noted similarities to the 1973 film Executive Action, but said Parallax was "a better use of similar material, however, because it tries to entertain instead of staying behind to argue."[9] In his review for The New York Times, Vincent Canby wrote, "Neither Mr. Pakula nor his screenwriters, David Giler and Lorenzo Semple, Jr., display the wit that Alfred Hitchcock might have used to give the tale importance transcending immediate plausibility. The moviemakers have, instead, treated their central idea so soberly that they sabotage credulity."[10] Joseph Kanon of The Atlantic found the film's subject pertinent: "what gives the movie its real force is the way its menace keeps absorbing material from contemporary life."[11]

Time magazine's Richard Schickel wrote, "We would probably be better off rethinking—or better yet, not thinking about—the whole dismal business, if only to put an end to ugly and dramatically unsatisfying products like The Parallax View."[12]

In 2006, Entertainment Weekly critic Chris Nashawaty wrote, "The Parallax View is a mother of a thriller... and Beatty, always an underrated actor thanks (or no thanks) to his off-screen rep as a Hollywood lothario, gives a hell of a performance in a career that's been full of them."[13]

Alexander Kaplan at Film Score Monthly wrote, "Beatty brought his relaxed, low-key charm[,] making his character’s fate even more shocking, while the supporting cast provided ... memorable performances, including Paula Prentiss’s heartbreakingly terrified reporter[.] ... Pakula observed that Frady 'imagines the most bizarre kind of plots, (but) is destroyed by a truth worse than anything he could have imagined.' The film’s ending ... suggests that Parallax may have been onto Frady the whole time, another subversion of his heroic status. Even the hero’s name is unheroic, 'Joe Frady' suggesting a mocking mixture of Dragnet’s Joe Friday and the schoolyard taunt [']fraidy cat.'"[14]

The motion picture won the Critics Award at the Avoriaz Film Festival (France) and was nominated for the Edgar Allan Poe Award for Best Motion Picture. Gordon Willis won the Award for Best Cinematography from the National Society of Film Critics (USA).

Reviewing films depicting political assassination conspiracies for The Guardian, director Alex Cox called the film the "best JFK conspiracy movie".[15] Film critic Matt Zoller Seitz has called it "a damn near perfect movie".[16]

See also

[edit]- Arlington Road

- Assassinations in fiction

- List of American films of 1974

- List of cult films

- List of films featuring surveillance

- The Manchurian Candidate

- Permindex

References

[edit]- ^ "AFI|Catalog".

- ^ Singer, Loren (1970), The Parallax View. New York: Dell, ISBN 1401069029

- ^ a b Kirshner, Jonathan (July 27, 2016). "In the Dark". Slate. Archived from the original on October 31, 2020. Retrieved September 20, 2020.

- ^ Lefcourt, Peter; Shapiro, Laura (2009-02-18). The First Time I Got Paid For It: Writers' Tales From The Hollywood Trenches. Hachette Books. ISBN 978-0-7867-4522-7. Archived from the original on 2023-01-21. Retrieved 2022-07-29.

- ^ a b Semley, John (November 20, 2013). "The Best Scene in the Best Conspiracy Thriller Ever". Esquire. Archived from the original on December 5, 2020. Retrieved September 20, 2020.

- ^ Smith, Kyle (August 14, 2020). "The Political Noir for the Age of Assassination". National Review. Archived from the original on September 24, 2020. Retrieved September 20, 2020.

- ^ "The Parallax View". Rotten Tomatoes. Archived from the original on September 27, 2020. Retrieved June 15, 2024.

- ^ "The Parallax View". Metacritic. Archived from the original on 2020-11-15. Retrieved 2021-01-01.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (June 14, 1974). "The Parallax View". Chicago Sun-Times. Archived from the original on November 12, 2008. Retrieved October 1, 2009.

- ^ Canby, Vincent (June 20, 1974). "The Parallax View". The New York Times. Archived from the original on January 21, 2023. Retrieved October 1, 2009.

- ^ Simon, Art (July 21, 2017). "In The Parallax View, Conspiracy Goes All the Way to the Top—and Beyond". Slate. Archived from the original on October 31, 2020. Retrieved September 20, 2020.

- ^ Schickel, Richard (July 8, 1974). "Paranoid Thriller". Time. Archived from the original on December 22, 2008. Retrieved October 1, 2009.

- ^ Nashawaty, Chris (July 12, 2006). "The Parallax View and other great Beatty roles". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on October 13, 2022. Retrieved October 7, 2022.

- ^ "The Parallax View". Film Score Monthly. 2010. Retrieved May 29, 2023.

- ^ Cox, Alex (November 19, 2013). "The Parallax View: a JFK conspiracy film that gets it right". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on October 31, 2020. Retrieved September 20, 2020.

- ^ @mattzollerseitz (March 8, 2013). "THE PARALLAX VIEW (1974). Dir: Alan J. Pakula. DP: Gordon Willis. A damn near perfect movie" (Tweet) – via Twitter.

External links

[edit]- The Parallax View at IMDb

- DVD Savant review of the montage

- The Parallax View: Dark Towers an essay by Nathan Heller at the Criterion Collection

- 1974 films

- 1970s political thriller films

- 1970s psychological thriller films

- American political thriller films

- Films directed by Alan J. Pakula

- Films with screenplays by David Giler

- Films about assassinations

- Films about conspiracy theories

- Paramount Pictures films

- Films set in Seattle

- Films set in Los Angeles

- Films about journalists

- Films based on American novels

- Films with screenplays by Robert Towne

- Films with screenplays by Lorenzo Semple Jr.

- Films scored by Michael Small

- American neo-noir films

- 1970s English-language films

- 1970s American films

- English-language thriller films